Generative AI in Gaming

Adaptive Storylines and Interactive NPCs

Published: 19.11.2025

Estimated reading time: 30 minutes

Imagine a role-playing game that writes itself as you play—quests twist in unexpected ways based on your actions, and characters respond with unscripted dialogue as if controlled by real people. Recent advances in generative AI are turning this vision into reality. AI models can now generate entire 3D worlds from a single prompt and populate them with interactive non-player characters (NPCs) that learn and adapt. Game developers are tapping these technologies to create adaptive storylines that branch organically and interactive NPCs with believable personalities. The result is a new breed of games that feel less like pre-programmed software and more like living, responsive worlds.

Adaptive Storylines: Games That Rewrite Themselves

Traditional game narratives are largely static – designers script a finite set of story branches or dialogue choices. Generative AI changes this by allowing the story content to be created dynamically in real time. Large Language Models (LLMs) can serve as storyteller AIs, generating fresh dialogue, quest descriptions, and plot twists on the fly. For players, this means the storyline can adapt to their choices in ways that weren’t explicitly predetermined. Every playthrough can unveil new events or endings because the narrative isn’t limited to a fixed script.

Early experiments have already shown the potential. AI Dungeon, for example, used an LLM to improvise text adventures where the player could type any action and the story would continue in a coherent way. Mainstream studios are also exploring AI-driven content: Ubisoft’s Ghostwriter tool assists writers by generating draft dialogue barks for NPCs, hinting at a future where an AI “dungeon master” could generate entire side quests or world events during gameplay. In an AI-augmented RPG, a simple side quest to find a lost sword might evolve into a personal saga because the AI spins out a backstory about the sword’s origin or introduces a rival character dynamically. This level of narrative responsiveness boosts player agency and replayability – the game truly becomes your story.

Crucially, adaptive storytelling AI isn’t just making up random plots; it can be guided by prompt engineering and game logic to stay within believable bounds. Designers define the setting, characters, and possible themes in advance, and the AI then expands on those within set parameters. For example, a prompt to the AI might include the current world state (“The kingdom is on the brink of war after the king’s assassination”) and character motivations, so the generated plot developments remain consistent with the game lore. Through careful prompt design and iterative generation, AI-driven narratives can maintain coherence even as they branch in novel directions. The outcome is a fluid storyline that reacts to the player’s actions: rescue an NPC, and the AI might weave that deed into later dialogues or spawn a gratitude-driven quest; slay a monster with a rare poison, and an AI narrator could later recall that detail when you face a boss with a weakness to it. The story becomes an emergent experience crafted in collaboration between the player’s decisions and the AI’s creativity.

Interactive NPCs Powered by AI

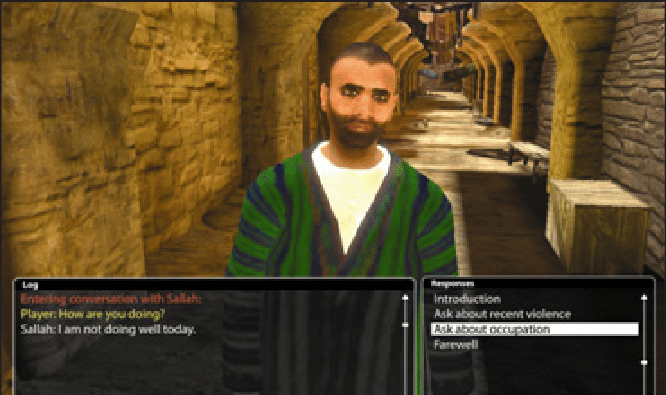

Perhaps the most visible leap in AI-driven gaming is the rise of intelligent NPCs. These are game characters enhanced by generative models so they can engage the player in free-form conversation and exhibit believable behavior beyond rigid scripts. Instead of delivering one-line responses on repeat, an AI-powered NPC can understand a wide range of player inputs (text or voice) and respond in natural, context-aware language. Moreover, these NPCs can remember past interactions and adjust their demeanor accordingly, giving a sense of persistent relationships in the game.

By leveraging LLMs as their “brains,” NPCs can be imbued with personalities and goals defined in prose rather than code. For example, a developer might create an innkeeper NPC by writing a brief description (prompt) of her background: “Elena is a weary but kind innkeeper who lost her son in the war; she’s talkative with travelers but grows somber if the war is mentioned.” With this prompt guiding the model, Elena’s character emerges in gameplay: she might greet players warmly, share rumors about the town, and if a player brings up war, her responses will organically reflect sadness or a personal story. All of this dialogue is generated on demand by the AI, not pre-written line by line.

It’s not just talk, either—AI NPCs can exhibit goal-driven behaviors. If equipped with memory and a planning routine, an NPC can pursue objectives in the game world semi-autonomously. In a striking research demonstration, Stanford researchers populated a simulation with 25 AI-controlled characters given simple backstories and daily routines. The result was a bustling virtual town where these agents woke themselves up, went to work, socialized with each other, and even coordinated a Valentine’s Day party entirely on their own. This kind of emergent NPC behavior was driven by each agent’s prompts and an LLM that let them plan and react like individual personalities. It’s easy to see the game implications: townsfolk in an RPG could have unscripted conversations with each other, form opinions about the player based on past deeds, or team up to solve problems—all without direct scripting, just AI simulation.

Several companies are racing to make AI-driven characters accessible to game developers. Platforms like Inworld AI, Convai, and Charisma.ai provide tools to design conversational NPCs with memory, emotion, and voice integration. These systems typically layer additional AI models on top of base LLMs to give characters emotional range, factual knowledge, and consistency. For instance, the AI engine might combine a large language model (for general dialogue) with databases of game lore or a knowledge graph of the game world, so that NPCs can speak accurately about local facts and stay “in character.” Developers can integrate these AI characters into game engines like Unity or Unreal through SDKs, making it relatively straightforward to bring a virtual shopkeeper or quest-giver to life. Meanwhile, tech giants are also pushing the envelope: NVIDIA’s ACE for Games toolkit offers an end-to-end pipeline for AI NPCs, including speech recognition (so the NPC can listen to the player’s voice), LLM-driven dialogue, and realistic text-to-speech to voice the character’s lines. In a demo showcased at Computex, an NPC in a cyberpunk-themed ramen shop carried on a plausible real-time conversation with the player about the menu and the state of the city, complete with facial animations and spoken dialogue. The excitement around these interactive NPCs is that they make game worlds feel significantly more immersive and unscripted. A player might spend hours just chatting with an interesting AI character, or receive dynamically generated hints and backstory from an NPC based on what the player has or hasn’t done in the game.

Under the Hood: Key Technologies Enabling Generative Gameplay

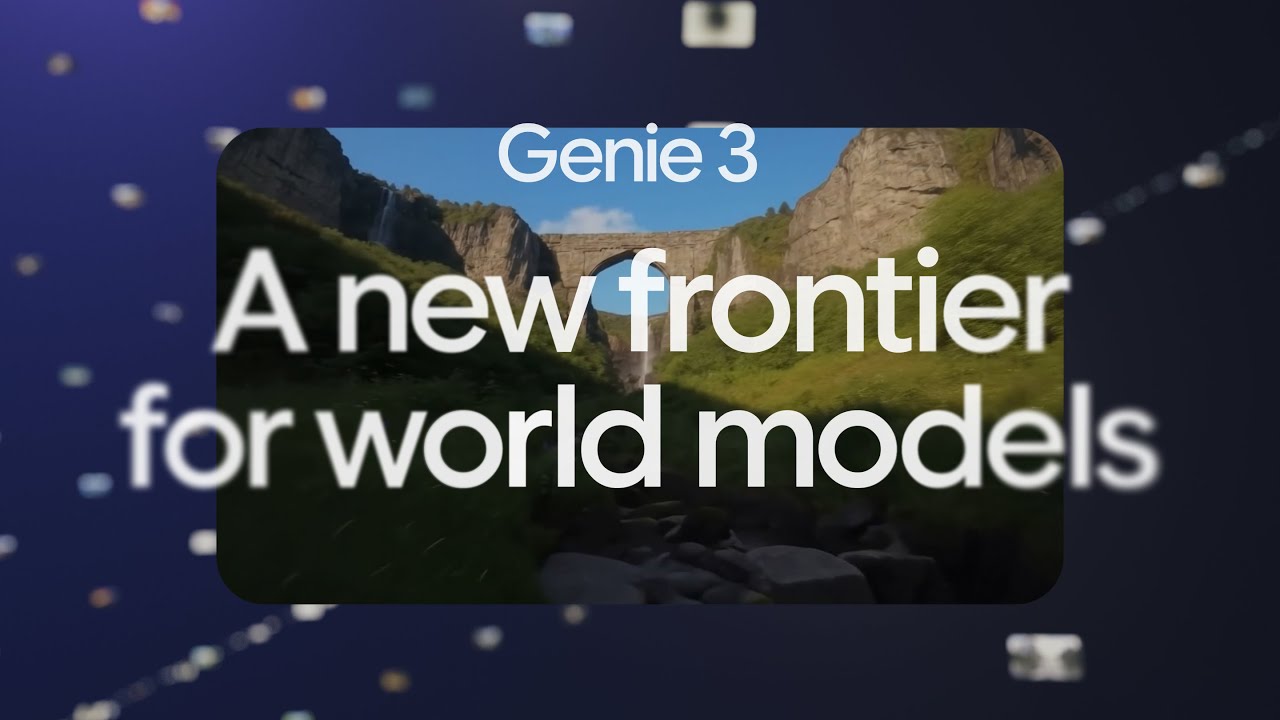

Behind these new adaptive games are several breakthrough AI technologies. Beyond Google DeepMind’s much-publicized Genie 3 world model, which generates entire 3D environments from text, a range of tools are expanding what’s possible in game AI. Here are some of the most important technologies driving this shift:

Generalist Agents and Multi-Agent Systems (SIMA and beyond)

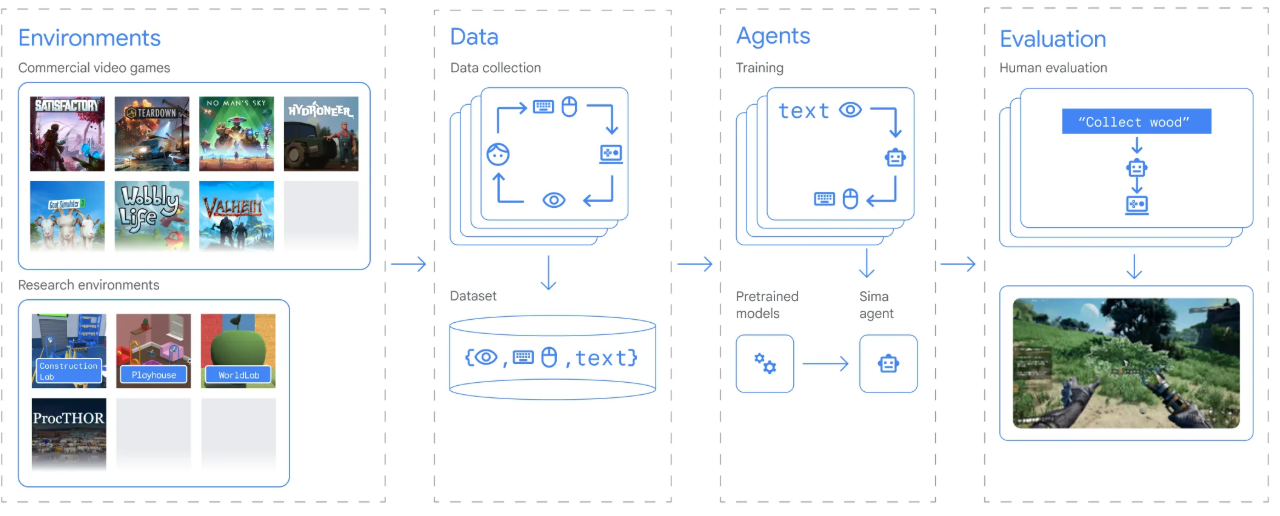

A major development comes from AI agents that can navigate and interact with complex game worlds in a human-like way. DeepMind’s SIMA project (short for Scalable Instructable Multi-Agent) is a prime example. SIMA is essentially a general-purpose game-playing agent: it was trained on a plethora of game scenarios and learned to follow natural-language instructions across different 3D environments. In practice, this means you could drop a SIMA-based agent into a sandbox game and tell it “collect wood and build a shelter” or “find the red key to open the door”, and it will figure out how to execute the task, even in a game it’s never seen before. Early versions of SIMA could only accomplish simple goals with modest success rates, but the latest iteration (SIMA 2, enhanced by Google’s Gemini LLM) shows human-level competency in many cases. It can understand high-level commands, then reason and plan steps to achieve them, all while controlling a game character to perform the needed actions. For gamers, such generalist AI agents hint at NPC companions that are far more autonomous and adaptable.

A SIMA-like NPC ally in an open-world game might take initiative to scout areas, collect resources, or cover the player in combat, with only a hint of guidance rather than explicit waypoints. Moreover, multi-agent systems (multiple AIs interacting) open the door to unscripted group dynamics – think of AI squadmates coordinating tactics on their own, or rival AI factions strategizing against each other in a strategy game. These agents operate via a combination of reinforcement learning (learning by trial and error in simulated play) and advanced reasoning from language models, merging raw gameplay skill with high-level reasoning. While still largely in research, projects like SIMA demonstrate that AI can be more than just a content generator – it can be an adaptive decision-maker within game worlds, making NPCs smarter and game systems more responsive.

Prompt-Driven NPC Behavior Generation

Traditionally, designing an NPC’s behavior meant hard-coding decision trees or writing numerous dialogue lines. Prompt-driven generation flips this approach: developers write descriptive prompts that set the character’s profile and let the AI model generate appropriate behavior and dialogue. This approach is akin to giving the NPC a written personality and backstory, then allowing it to improvise.

As mentioned, simply describing an NPC in a prompt (including their traits, mood, knowledge, and speaking style) is enough for a large language model to emulate that character in conversation.

Developers can also specify goals or rules in the prompt, for example: “Ragnar is a guard who must not allow the player into the castle without a royal seal. He is polite but firm, and he will offer a hint about how to obtain a seal if the player befriends him.” From this single prompt, the AI can handle a wide range of player interactions: if the player tries to sneak past, Ragnar might warn them; if the player asks about the seal, Ragnar might divulge a clue or a side-quest to get one, and he’ll maintain that polite-but-firm tone throughout. All these responses are generated dynamically following the guiding prompt.

The key technologies here are large language models (like GPT-4, PaLM, or open-source LLMs) possibly fine-tuned for dialogue, often augmented with memory modules. Memory is crucial: it enables the NPC to refer to past events (“As I told you yesterday…”) and thus maintain continuity in long-term interactions. Some systems implement this by keeping a summary of recent conversations or important facts and prepending it to the prompt each time the NPC “speaks.” Others use vector databases to let the AI look up game lore or character knowledge on the fly. Additionally, game-specific AI platforms enhance prompt-driven NPCs with emotion and behavior models.

This might include an AI emotion model that tracks the NPC’s mood based on recent interactions (so that, say, repeated player insults make the NPC increasingly hostile), or a planning component that decides when the NPC should perform a non-verbal action (like wave, pace nervously, etc.). All of these aspects can be controlled or nudged via prompt elements and system-level instructions. For designers, prompt-driven NPC creation is powerful: it’s much faster to iterate on a character concept by tweaking a text description than to rewrite code. It also allows for far greater variety in expressions because the AI isn’t limited to pre-written lines. The trade-off is that controlling an AI with prompts can be imprecise; it may sometimes say or do things unexpectedly. That’s why developers use techniques like example dialogs in the prompt (to demonstrate the desired style) and impose content filters or policies so the NPC doesn’t go out of bounds. When done right, the result is an NPC that feels surprisingly human and contextually aware, crafted more by writing than by coding.

Diffusion-Based World and Scene Generation

While language models handle text and logic, diffusion models and other generative visual models are tackling the graphical side of gaming. Diffusion models (like the popular Stable Diffusion) are capable of creating images from text prompts by iteratively refining random noise into a coherent picture. In gaming, they’re being used for everything from concept art to texture creation—and now, even to generate entire scenes and levels.

For example, imagine being able to type “a gloomy medieval dungeon with flickering torches and wet stone walls” and having a game engine directly generate a unique dungeon level layout or at least the art assets for it. Diffusion models are making strides toward this kind of on-demand scene creation. Researchers have already demonstrated prototype “AI game engines” where a diffusion model generates game frames in real time as an agent moves through the environment.

One recent project, fittingly called DIAMOND (Diffusion as a Model of Environment), trained a diffusion model on classic 2D video games and showed that it could generate new playable levels of those games. Essentially, the AI would imagine what the next screen looks like and update it as the player/agent moves or takes actions, creating a continuous, playable world. It’s like a dream that unfolds around the player, consistent enough to be a game environment. Although these AI-generated Atari-like games were simple and run at lower resolution than traditional engines, the fact that it’s possible to have a neural network serve as a real-time game simulator is a huge breakthrough.

In more immediate practical use are diffusion models for asset generation. Game studios are beginning to use diffusion-based tools to create concept art, character portraits, item illustrations, even textures for 3D models. For instance, an artist might generate dozens of variations of a sci-fi spaceship using a text-to-image model, then pick one as a starting point for the final design. Tools like Scenario GG let developers train custom diffusion models on their game’s art style, so they can generate new props or character skins that fit seamlessly into their world. Unity’s Muse AI, recently introduced, integrates text-to-image generation right into the Unity editor – developers can prompt it for a “rocky terrain texture” or “neon-lit storefront sign” and get usable assets without leaving their workspace. Similarly, NVIDIA Picasso and other emerging platforms promise to generate 3D objects or even entire 3D scenes through diffusion-like techniques (though 3D generation is still an evolving area).

Another application is using image-generation to enhance procedural generation: for example, a level layout might be algorithmically designed, but then a diffusion model could render detailed textures or variations of that layout’s appearance to make each run of a roguelike game look visually distinct while preserving the same map structure. By leveraging diffusion models, game worlds can be crafted faster and with more diversity, and even personalized visuals per player become possible (like generating a unique banner symbol for each player’s guild using an AI artist).

It’s worth noting that while diffusion models can create stunning content, they require careful prompting and often human tuning to get the desired result. They also need to be optimized to run efficiently if they’re to be part of a live game (generating an image can be slow and GPU-intensive). However, progress in model optimization and dedicated hardware (GPUs, TPUs, etc.) is rapidly improving this. We’re heading toward a future where much of a game’s art and even level design might be generated or assisted by AI, either during development or even in real time as the game runs. And beyond saving labor, this unlocks fundamentally new game design possibilities: truly infinite worlds where no two dungeons or galaxies look the same, because they’re generated on demand by the AI instead of pulled from a fixed library of artist-made content. Combined with the narrative and NPC advances, diffusion-based world generation points toward games that build themselves around the player, both in story and in scenery.

Prompt Engineering Tips for Game Designers

Creating quality adaptive content with AI is as much an art as a science. Designers need to speak the AI’s language through effective prompts and data setups. Poorly crafted prompts can lead to NPCs going off-theme or narratives that wander into nonsense. Below are some practical prompt-engineering tips to help control character behavior, dialogue tone, and world consistency in generative games:

Define Clear Character Profiles and Boundaries: When designing an AI-driven NPC, spend time writing a detailed character profile in the prompt. Include the character’s role, personality traits, backstory, and dos and don’ts. For example: “Sir Gareth is a knight who is honorable and verbose. He never uses slang. He hates black magic.” This gives the AI a firm template to emulate. Clearly state any forbidden behaviors or topics as well if needed (e.g. “do not reveal puzzle solutions outright”). A well-defined role acts like a rulebook that keeps the NPC’s behavior consistent over time.

Guide the Dialogue Tone with Examples: If you want the AI to maintain a certain tone or style, illustrate it. In prompts or system messages, you can provide one or two example exchanges in the desired voice. For instance, to ensure an NPC speaks in old-English formality, you might include a sample line of dialogue like, “Good morrow, traveler. How might I be of service on this fine eve?” By showing the model what “good” output looks like, you steer its responses. You can also explicitly name a style: “The narrator’s tone should be ominous and poetic, like a dark fairy tale.” The AI will take cues from these instructions to keep the dialogue on brand. Essentially, be as explicit as possible about the tone, mood, and format of the outputs you want.

Maintain Context and World Consistency: Generative models have no inherent memory of game state unless you provide it. Always include key context in the prompt. This might mean appending a summary of recent important events whenever you call the AI to continue a storyline or adding a snippet of the game’s lore to the NPC’s prompt so it doesn’t contradict known facts. A good practice is to create a running “world state” text that gets updated and fed into the AI. For example: “[World Context: The player is a member of the Thieves Guild and recently saved the Prince from assassins. The city is on high alert.]” If an NPC knows these facts, it won’t mistakenly treat the player like a nobody, and the narrative will feel coherent. Consistency also means verifying the AI’s outputs and possibly using tools to cross-check for contradictions (some developers use symbolic logic or databases to ensure factual consistency in generated content). In short, never assume the AI remembers anything—always reinforce important details through the prompt to keep the narrative logically consistent.

By following these prompt strategies, game designers can significantly tame the chaos of generative systems. Think of prompt engineering as directing an improv actor: you set the scene, give them a character, perhaps feed them some lines or cues, and then let them perform—occasionally nudging them back on script if they stray. With iterative testing and refinement of prompts, you can achieve a reliable balance where the AI adds creativity and variability while still aligning with your design vision.

AI Tools and Platforms for Generative Game Development

As generative AI makes its way into game development, an ecosystem of tools and platforms has emerged to support different aspects of content creation. Below is a comparison of leading AI solutions in three key categories: world models, dialogue engines, and generative art tools. These platforms can help game creators implement adaptive narratives, smarter NPCs, and on-demand asset generation without reinventing the wheel:

| Category | Notable Tools/Platforms | Capabilities for Games |

|---|---|---|

| Generative World Models | DeepMind Genie 3 MineDojo Google SIMA (research) | Procedurally generates interactive game environments from high-level prompts. For example, Genie 3 can create a 3D world (terrain, objects, physics) in real time based on a text description. These world models enable rapid prototyping of levels and endless exploration, doubling as simulation platforms for AI agents. MineDojo and similar efforts integrate AI agents in sandbox worlds (e.g. Minecraft) to learn tasks, producing synthetic environments and scenarios on demand. |

| Dialogue & NPC Engines | Inworld AI; Convai Charisma.ai OpenAI GPT API | Powers dynamic NPC conversations and behavior. These platforms provide a pipeline to define characters through natural language and plug them into games. They typically include memory, emotion, and voice support. For instance, Inworld allows developers to script an NPC’s personality and knowledge base, then handles the real-time dialogue generation and even gestures. Some, like Convai, offer ready integration with game engines so your NPCs can listen (speech-to-text) and talk (text-to-speech) fluidly. The result is interactive characters that respond realistically to players, with minimal manual dialogue writing. |

| Generative Art & Scenes | Stable Diffusion Midjourney Scenario GG Unity Muse | Creates visual game content from text prompts. These tools can generate concept art, textures, sprites, item icons, and even 3D model ideas. Stable Diffusion (open-source) and Midjourney (hosted) are popular for concept and 2D asset generation – e.g. auto-creating dozens of creature designs to inspire an artist. Scenario GG specializes in game assets, allowing training on your art style for consistent outputs. Unity’s Muse is built into the engine for instant generation of assets or environments during development. Using generative art tools, small teams can produce high-quality visual content quickly, and even automate the creation of variant assets (like personalized character portraits or infinite level backgrounds) for greater visual diversity in-game. |

How to read this table: Each category addresses a different part of game development enhanced by AI. World models focus on the environment: they generate the spaces and mechanics of the game world. Dialogue/NPC engines focus on characters and interaction: they drive what NPCs say and do. Generative art tools focus on visuals: they produce the look and feel assets of the game. Depending on your project’s needs, you might use one or all of these in combination — for example, using a world model to create levels, an NPC engine to give your characters minds, and an art generator to decorate the world’s textures and concept art.

Ethical Considerations in AI-Driven Games

The use of generative AI in gaming brings tremendous creative upsides, but it also raises important ethical and practical issues that designers must address. Two of the most pressing concerns are bias in generated content and player data privacy:

Bias and Representation

AI models learn from vast datasets, and unfortunately these data often contain societal biases or stereotypes. In the context of a game, this could manifest in an NPC generating dialogue that is unintentionally prejudiced, culturally insensitive, or just reinforcing clichés (imagine an AI-driven character that always makes assumptions about the player’s character based on fantasy “race” in a way that maps uncomfortably to real-world stereotypes).

Biased content can diminish player experience at best and cause harm or offense at worst. To combat this, developers need to implement content filtering and moderation for AI outputs. Many AI platforms provide toxicity filters or bias detection tools that can catch problematic language before it reaches the player. Additionally, prompt design has a role to play: if you explicitly instruct an NPC to behave respectfully and avoid certain topics, the AI is more likely to comply. Diversity in the training data and in the game design team itself can also help by identifying potential issues early (for example, making sure a generative narrative doesn’t always cast certain groups as villains).

There’s also an emerging idea of regulatory prompts – essentially, adding a layer to the AI system that checks outputs against inclusion or bias guidelines (similar to how some companies do AI auditing). Ultimately, maintaining an inclusive and respectful game world when using AI is an active process; it requires testing the AI extensively for unwanted biases and continuously refining both the model and the prompts to correct any skewed behavior.

While generative AI can amplify creativity, we must ensure it doesn’t also amplify social biases – the lore and characters it creates should be as diverse and respectful as the real world (or more so, aspirationally).

Player Data and Privacy

Adaptive AI systems often rely on collecting and analyzing player data to tailor the experience. For instance, an AI narrative engine might track the player’s choices or even emotional cues (in future AR/VR setups) to adjust the storyline, and AI NPCs might log previous conversations to remember the player’s personal details or play style. This personalized approach blurs the line between game content and player data.

Privacy concerns arise if these data (chat logs, behavioral profiles, voice recordings, etc.) are stored or processed insecurely, or if they are sent to third-party AI services in the cloud. Players might justifiably worry: what happens to all the things I’ve said to this AI character? Could my in-game conversations be used for marketing, or accessed by others? To address this, developers need to be transparent and privacy-conscious in their implementation of AI.

Best practices include anonymizing player data wherever possible, only retaining data needed for the gameplay experience, and giving players control (such as the ability to reset an NPC’s memory or opt out of certain data collection). Many are looking toward on-device AI as a solution, where the generative model runs locally on the player’s console/PC so that personal data never leaves the device.

This is becoming more feasible as smaller, optimized models and powerful consumer hardware become available. Additionally, compliance with regulations like GDPR is crucial – if your game has players generate any personal content (even just their voice chat being transcribed by an AI), you need clear user consent and data handling policies. Beyond legal requirements, there’s an ethical responsibility to treat players’ interactions with AI characters as private moments, not as telemetry to exploit.

As a design principle, the adaptive systems should use player data solely to enhance the gameplay for that player and not as a side product. Earning player trust will be vital for AI-driven games; if people suspect the friendly NPC is really a surveillance device, the magic of the experience quickly fades.

Ethical Prompt Engineering

Avoiding Bias, Hallucination and Infringement

The Road Ahead

Generative AI is poised to fundamentally expand what games can do. We are witnessing the early steps of games becoming open-ended, collaborative experiences between human creativity and AI creativity. A decade ago, the idea of a player having a natural conversation with an NPC or wandering a completely AI-generated world would have sounded like science fiction. Today, demos and prototypes have proven these concepts, and the coming years will be about refining and integrating them into mainstream titles. There are still challenges to solve – from technical constraints like model performance and cost, to design questions about maintaining game balance when content can change dynamically. Yet, the trajectory is clear: games are heading toward unprecedented levels of immersion and personalization.

As developers, embracing generative AI means rethinking some of our old assumptions. Game design may shift from meticulously hand-crafting every moment to orchestrating AI systems that create moments on the fly. Players, in turn, will demand transparency and fairness from these AI-driven experiences, expecting them to be as inclusive, fun, and respectful as any traditionally crafted game. By keeping ethical considerations in focus and using these tools thoughtfully, we can ensure that the rise of adaptive storylines and interactive NPCs enhances gaming in a positive way.

It’s an exciting time to be both a gamer and a creator. We stand on the cusp of games that can literally invent new adventures indefinitely, tailored to each player’s style and whims. In these worlds, no two heroes’ journeys will be the same. Generative AI is the key unlocking this future of limitless play – a future where the game engine is as much a storyteller and collaborator as it is a piece of software. The games of tomorrow won’t just be played; they’ll be co-created every time you hit “Start”.

Sources

- Daniel Dominguez, “DeepMind Launches Genie 3, a Text-to-3D Interactive World Model,” InfoQ (Aug 18, 2025). – Overview of DeepMind’s Genie 3 world model, which generates interactive 3D environments from text prompts in real time, with persistent object permanence and physics consistency.

- Rebecca Bellan, “Google’s SIMA 2 agent uses Gemini to reason and act in virtual worlds,” TechCrunch (Nov 13, 2025). – Article on SIMA 2, DeepMind’s generalist game agent, detailing how it follows instructions across games, reasons with the Gemini language model, and even navigates new photorealistic worlds generated by Genie.

- Eric Duan, “AI NPCs: The Future of Game Characters,” Naavik Digest (Dec 1, 2024). – In-depth exploration of AI-driven NPCs, including how companies like Inworld create NPC “brains” via prompts, the integration with tools like NVIDIA ACE for voice and animation, and early use cases in games and platforms like Roblox.

- Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI, “Computational Agents Exhibit Believable Humanlike Behavior,” (Sep 21, 2023). – Stanford HAI news piece on the generative agents research, where 25 AI-powered characters in a SIMS-like environment behaved with realistic routines and memory, highlighting the potential for emergent NPC behavior and social interactions driven by LLMs.

- Zian (Andy) Wang, “How Diffusion Models Are Reimagining Game Environments: DIAMOND,” Deepgram Blog (Feb 7, 2025). – Explains the use of diffusion models for real-time game environment generation, discussing the DIAMOND approach that generates playable Atari game levels and even a 3D Counter-Strike example, as well as how diffusion-based world models can supply synthetic training data for reinforcement learning agents.